Swapchain

Code: main.rs

Vulkan does not have the concept of a "default framebuffer", hence it requires an infrastructure that will own the buffers we will render to before we visualize them on the screen. This infrastructure is known as the swapchain and must be created explicitly in Vulkan. The swapchain is essentially a queue of images that are waiting to be presented to the screen. Our application will acquire such an image to draw to it, and then return it to the queue. How exactly the queue works and the conditions for presenting an image from the queue depend on how the swapchain is set up, but the general purpose of the swapchain is to synchronize the presentation of images with the refresh rate of the screen.

Checking for swapchain support

Not all graphics cards are capable of presenting images directly to a screen for various reasons, for example because they are designed for servers and don't have any display outputs. Secondly, since image presentation is heavily tied into the window system and the surfaces associated with windows, it is not actually part of the Vulkan core. You have to enable the VK_KHR_swapchain device extension after querying for its support. Also, like before, you need to import the vulkanalia extension trait for VK_KHR_swapchain:

// Note: This trait was called `KhrSwapchainExtension` in versions of `vulkanalia` prior to `v0.31.0`.

use vulkanalia::vk::KhrSwapchainExtensionDeviceCommands;

Then we'll first extend the check_physical_device function to check if this extension is supported. We've previously seen how to list the extensions that are supported by a vk::PhysicalDevice, so doing that should be fairly straightforward.

First declare a list of required device extensions, similar to the list of validation layers to enable.

const DEVICE_EXTENSIONS: &[vk::ExtensionName] = &[vk::KHR_SWAPCHAIN_EXTENSION.name];

Next, create a new function check_physical_device_extensions that is called from check_physical_device as an additional check:

unsafe fn check_physical_device(

instance: &Instance,

data: &AppData,

physical_device: vk::PhysicalDevice,

) -> Result<()> {

QueueFamilyIndices::get(instance, data, physical_device)?;

check_physical_device_extensions(instance, physical_device)?;

Ok(())

}

unsafe fn check_physical_device_extensions(

instance: &Instance,

physical_device: vk::PhysicalDevice,

) -> Result<()> {

Ok(())

}

Modify the body of the function to enumerate the extensions and check if all of the required extensions are amongst them.

unsafe fn check_physical_device_extensions(

instance: &Instance,

physical_device: vk::PhysicalDevice,

) -> Result<()> {

let extensions = instance

.enumerate_device_extension_properties(physical_device, None)?

.iter()

.map(|e| e.extension_name)

.collect::<HashSet<_>>();

if DEVICE_EXTENSIONS.iter().all(|e| extensions.contains(e)) {

Ok(())

} else {

Err(anyhow!(SuitabilityError("Missing required device extensions.")))

}

}

Now run the code and verify that your graphics card is indeed capable of creating a swapchain. It should be noted that the availability of a presentation queue, as we checked in the previous chapter, implies that the swapchain extension must be supported. However, it's still good to be explicit about things, and the extension does have to be explicitly enabled.

Enabling device extensions

Using a swapchain requires enabling the VK_KHR_swapchain extension first. Enabling the extension just requires a small change to our list of device extensions in the create_logical_device function. Initialize our list of device extensions with a list of null-terminated strings constructed from DEVICE_EXTENSIONS:

let mut extensions = DEVICE_EXTENSIONS

.iter()

.map(|n| n.as_ptr())

.collect::<Vec<_>>();

Querying details of swapchain support

Just checking if a swapchain is available is not sufficient, because it may not actually be compatible with our window surface. Creating a swapchain also involves a lot more settings than instance and device creation, so we need to query for some more details before we're able to proceed.

There are basically three kinds of properties we need to check:

- Basic surface capabilities (min/max number of images in swapchain, min/max width and height of images)

- Surface formats (pixel format, color space)

- Available presentation modes

Similar to QueueFamilyIndices, we'll use a struct to pass these details around once they've been queried. The three aforementioned types of properties come in the form of the following structs and lists of structs:

#[derive(Clone, Debug)]

struct SwapchainSupport {

capabilities: vk::SurfaceCapabilitiesKHR,

formats: Vec<vk::SurfaceFormatKHR>,

present_modes: Vec<vk::PresentModeKHR>,

}

We'll now create a new method SwapchainSupport::get that will initialize this struct with all of the structs we need.

impl SwapchainSupport {

unsafe fn get(

instance: &Instance,

data: &AppData,

physical_device: vk::PhysicalDevice,

) -> Result<Self> {

Ok(Self {

capabilities: instance

.get_physical_device_surface_capabilities_khr(

physical_device, data.surface)?,

formats: instance

.get_physical_device_surface_formats_khr(

physical_device, data.surface)?,

present_modes: instance

.get_physical_device_surface_present_modes_khr(

physical_device, data.surface)?,

})

}

}

The meaning of these structs and exactly which data they contain is discussed in the next section.

All of the details are in the struct now, so let's extend check_physical_device once more to utilize this method to verify that swapchain support is adequate. swapchain support is sufficient for this tutorial if there is at least one supported image format and one supported presentation mode given the window surface we have.

unsafe fn check_physical_device(

instance: &Instance,

data: &AppData,

physical_device: vk::PhysicalDevice,

) -> Result<()> {

// ...

let support = SwapchainSupport::get(instance, data, physical_device)?;

if support.formats.is_empty() || support.present_modes.is_empty() {

return Err(anyhow!(SuitabilityError("Insufficient swapchain support.")));

}

Ok(())

}

It is important that we only try to query for swapchain support after verifying that the extension is available.

Choosing the right settings for the swapchain

If the conditions we just added were met then the support is definitely sufficient, but there may still be many different modes of varying optimality. We'll now write a couple of functions to find the right settings for the best possible swapchain. There are three types of settings to determine:

- Surface format (color depth)

- Presentation mode (conditions for "swapping" images to the screen)

- Swap extent (resolution of images in swapchain)

For each of these settings we'll have an ideal value in mind that we'll go with if it's available and otherwise we'll create some logic to find the next best thing.

Surface format

The function for this setting starts out like this. We'll later pass the formats field of the SwapchainSupport struct as argument.

fn get_swapchain_surface_format(

formats: &[vk::SurfaceFormatKHR],

) -> vk::SurfaceFormatKHR {

}

Each vk::SurfaceFormatKHR entry contains a format and a color_space member. The format member specifies the color channels and types. For example, vk::Format::B8G8R8A8_SRGB means that we store the B, G, R and alpha channels in that order with an 8 bit unsigned integer for a total of 32 bits per pixel. The color_space member indicates if the sRGB color space is supported or not using the vk::ColorSpaceKHR::SRGB_NONLINEAR flag.

For the color space we'll use sRGB if it is available, because it results in more accurate perceived colors. It is also pretty much the standard color space for images, like the textures we'll use later on. Because of that we should also use an sRGB color format, of which one of the most common ones is vk::Format::B8G8R8A8_SRGB.

Let's go through the list and see if the preferred combination is available:

fn get_swapchain_surface_format(

formats: &[vk::SurfaceFormatKHR],

) -> vk::SurfaceFormatKHR {

formats

.iter()

.cloned()

.find(|f| {

f.format == vk::Format::B8G8R8A8_SRGB

&& f.color_space == vk::ColorSpaceKHR::SRGB_NONLINEAR

})

.unwrap_or_else(|| formats[0])

}

If that also fails then we could rank the available formats based on how "good" they are, but in most cases it's okay to just settle with the first format that is specified hence .unwrap_or_else(|| formats[0]).

Presentation mode

The presentation mode is arguably the most important setting for the swapchain, because it represents the actual conditions for showing images to the screen. There are four possible modes available in Vulkan:

vk::PresentModeKHR::IMMEDIATE– Images submitted by your application are transferred to the screen right away, which may result in tearing.vk::PresentModeKHR::FIFO– The swapchain is a queue where the display takes an image from the front of the queue when the display is refreshed and the program inserts rendered images at the back of the queue. If the queue is full then the program has to wait. This is most similar to vertical sync as found in modern games. The moment that the display is refreshed is known as "vertical blank".vk::PresentModeKHR::FIFO_RELAXED– This mode only differs from the previous one if the application is late and the queue was empty at the last vertical blank. Instead of waiting for the next vertical blank, the image is transferred right away when it finally arrives. This may result in visible tearing.vk::PresentModeKHR::MAILBOX– This is another variation of the second mode. Instead of blocking the application when the queue is full, the images that are already queued are simply replaced with the newer ones. This mode can be used to render frames as fast as possible while still avoiding tearing, resulting in fewer latency issues than standard vertical sync. This is commonly known as "triple buffering", although the existence of three buffers alone does not necessarily mean that the framerate is unlocked.

Only the vk::PresentModeKHR::FIFO mode is guaranteed to be available, so we'll again have to write a function that looks for the best mode that is available:

fn get_swapchain_present_mode(

present_modes: &[vk::PresentModeKHR],

) -> vk::PresentModeKHR {

}

I personally think that vk::PresentModeKHR::MAILBOX is a very nice trade-off if energy usage is not a concern. It allows us to avoid tearing while still maintaining a fairly low latency by rendering new images that are as up-to-date as possible right until the vertical blank. On mobile devices, where energy usage is more important, you will probably want to use vk::PresentModeKHR::FIFO instead. Now, let's look through the list to see if vk::PresentModeKHR::MAILBOX is available:

fn get_swapchain_present_mode(

present_modes: &[vk::PresentModeKHR],

) -> vk::PresentModeKHR {

present_modes

.iter()

.cloned()

.find(|m| *m == vk::PresentModeKHR::MAILBOX)

.unwrap_or(vk::PresentModeKHR::FIFO)

}

Swap extent

That leaves only one major property, for which we'll add one last function:

fn get_swapchain_extent(

window: &Window,

capabilities: vk::SurfaceCapabilitiesKHR,

) -> vk::Extent2D {

}

The swap extent is the resolution of the swapchain images and it's almost always exactly equal to the resolution of the window that we're drawing to. The range of the possible resolutions is defined in the vk::SurfaceCapabilitiesKHR structure. Vulkan tells us to match the resolution of the window by setting the width and height in the current_extent member. However, some window managers do allow us to differ here and this is indicated by setting the width and height in current_extent to a special value: the maximum value of u32. In that case we'll pick the resolution that best matches the window within the min_image_extent and max_image_extent bounds.

fn get_swapchain_extent(

window: &Window,

capabilities: vk::SurfaceCapabilitiesKHR,

) -> vk::Extent2D {

if capabilities.current_extent.width != u32::MAX {

capabilities.current_extent

} else {

vk::Extent2D::builder()

.width(window.inner_size().width.clamp(

capabilities.min_image_extent.width,

capabilities.max_image_extent.width,

))

.height(window.inner_size().height.clamp(

capabilities.min_image_extent.height,

capabilities.max_image_extent.height,

))

.build()

}

}

We use the clamp function to restrict the actual size of the window within the supported range supported by the Vulkan device.

Creating the swapchain

Now that we have all of these helper functions assisting us with the choices we have to make at runtime, we finally have all the information that is needed to create a working swapchain.

Create a create_swapchain function that starts out with the results of these calls and make sure to call it from App::create after logical device creation.

impl App {

unsafe fn create(window: &Window) -> Result<Self> {

// ...

let device = create_logical_device(&instance, &mut data)?;

create_swapchain(window, &instance, &device, &mut data)?;

// ...

}

}

unsafe fn create_swapchain(

window: &Window,

instance: &Instance,

device: &Device,

data: &mut AppData,

) -> Result<()> {

let indices = QueueFamilyIndices::get(instance, data, data.physical_device)?;

let support = SwapchainSupport::get(instance, data, data.physical_device)?;

let surface_format = get_swapchain_surface_format(&support.formats);

let present_mode = get_swapchain_present_mode(&support.present_modes);

let extent = get_swapchain_extent(window, support.capabilities);

Ok(())

}

Aside from these properties we also have to decide how many images we would like to have in the swapchain. The implementation specifies the minimum number that it requires to function:

let image_count = support.capabilities.min_image_count;

However, simply sticking to this minimum means that we may sometimes have to wait on the driver to complete internal operations before we can acquire another image to render to. Therefore it is recommended to request at least one more image than the minimum:

let image_count = support.capabilities.min_image_count + 1;

We should also make sure to not exceed the maximum number of images while doing this, where 0 is a special value that means that there is no maximum:

let mut image_count = support.capabilities.min_image_count + 1;

if support.capabilities.max_image_count != 0

&& image_count > support.capabilities.max_image_count

{

image_count = support.capabilities.max_image_count;

}

Next, we need to specify how to handle swapchain images that will be used across multiple queue families. That will be the case in our application if the graphics queue family is different from the presentation queue. We'll be drawing on the images in the swapchain from the graphics queue and then submitting them on the presentation queue. There are two ways to handle images that are accessed from multiple queues:

vk::SharingMode::EXCLUSIVE– An image is owned by one queue family at a time and ownership must be explicitly transferred before using it in another queue family. This option offers the best performance.vk::SharingMode::CONCURRENT– Images can be used across multiple queue families without explicit ownership transfers.

If the queue families differ, then we'll be using the concurrent mode in this tutorial to avoid having to do the ownership chapters, because these involve some concepts that are better explained at a later time. Concurrent mode requires you to specify in advance between which queue families ownership will be shared using the queue_family_indices builder method. If the graphics queue family and presentation queue family are the same, which will be the case on most hardware, then we should stick to exclusive mode, because concurrent mode requires you to specify at least two distinct queue families.

let mut queue_family_indices = vec![];

let image_sharing_mode = if indices.graphics != indices.present {

queue_family_indices.push(indices.graphics);

queue_family_indices.push(indices.present);

vk::SharingMode::CONCURRENT

} else {

vk::SharingMode::EXCLUSIVE

};

As is tradition with Vulkan objects, creating the swapchain object requires filling in a large structure. It starts out very familiarly:

let info = vk::SwapchainCreateInfoKHR::builder()

.surface(data.surface)

// continued...

After specifying which surface the swapchain should be tied to, the details of the swapchain images are specified:

.min_image_count(image_count)

.image_format(surface_format.format)

.image_color_space(surface_format.color_space)

.image_extent(extent)

.image_array_layers(1)

.image_usage(vk::ImageUsageFlags::COLOR_ATTACHMENT)

The image_array_layers specifies the amount of layers each image consists of. This is always 1 unless you are developing a stereoscopic 3D application. The image_usage bitmask specifies what kind of operations we'll use the images in the swapchain for. In this tutorial we're going to render directly to them, which means that they're used as color attachment. It is also possible that you'll render images to a separate image first to perform operations like post-processing. In that case you may use a value like vk::ImageUsageFlags::TRANSFER_DST instead and use a memory operation to transfer the rendered image to a swapchain image.

.image_sharing_mode(image_sharing_mode)

.queue_family_indices(&queue_family_indices)

Next we'll provide the image sharing mode and indices of the queue families permitted to share the swapchain images.

.pre_transform(support.capabilities.current_transform)

We can specify that a certain transform should be applied to images in the swapchain if it is supported (supported_transforms in capabilities), like a 90 degree clockwise rotation or horizontal flip. To specify that you do not want any transformation, simply specify the current transformation.

.composite_alpha(vk::CompositeAlphaFlagsKHR::OPAQUE)

The composite_alpha method specifies if the alpha channel should be used for blending with other windows in the window system. You'll almost always want to simply ignore the alpha channel, hence vk::CompositeAlphaFlagsKHR::OPAQUE.

.present_mode(present_mode)

.clipped(true)

The present_mode member speaks for itself. If the clipped member is set to true then that means that we don't care about the color of pixels that are obscured, for example because another window is in front of them. Unless you really need to be able to read these pixels back and get predictable results, you'll get the best performance by enabling clipping.

.old_swapchain(vk::SwapchainKHR::null());

That leaves one last method, old_swapchain. With Vulkan it's possible that your swapchain becomes invalid or unoptimized while your application is running, for example because the window was resized. In that case the swapchain actually needs to be recreated from scratch and a reference to the old one must be specified in this method. This is a complex topic that we'll learn more about in a future chapter. For now we'll assume that we'll only ever create one swapchain. We could omit this method since the underlying field will default to a null handle, but we'll leave it in for completeness.

Now add an AppData field to store the vk::SwapchainKHR object:

struct AppData {

// ...

swapchain: vk::SwapchainKHR,

}

Creating the swapchain is now as simple as calling create_swapchain_khr:

data.swapchain = device.create_swapchain_khr(&info, None)?;

The parameters are the swapchain creation info and optional custom allocators. No surprises there. It should be cleaned up in App::destroy before the device:

unsafe fn destroy(&mut self) {

self.device.destroy_swapchain_khr(self.data.swapchain, None);

// ...

}

Now run the application to ensure that the swapchain is created successfully! If at this point you get an access violation error in vkCreateSwapchainKHR or see a message like Failed to find 'vkGetInstanceProcAddress' in layer SteamOverlayVulkanLayer.dll, then see the FAQ entry about the Steam overlay layer.

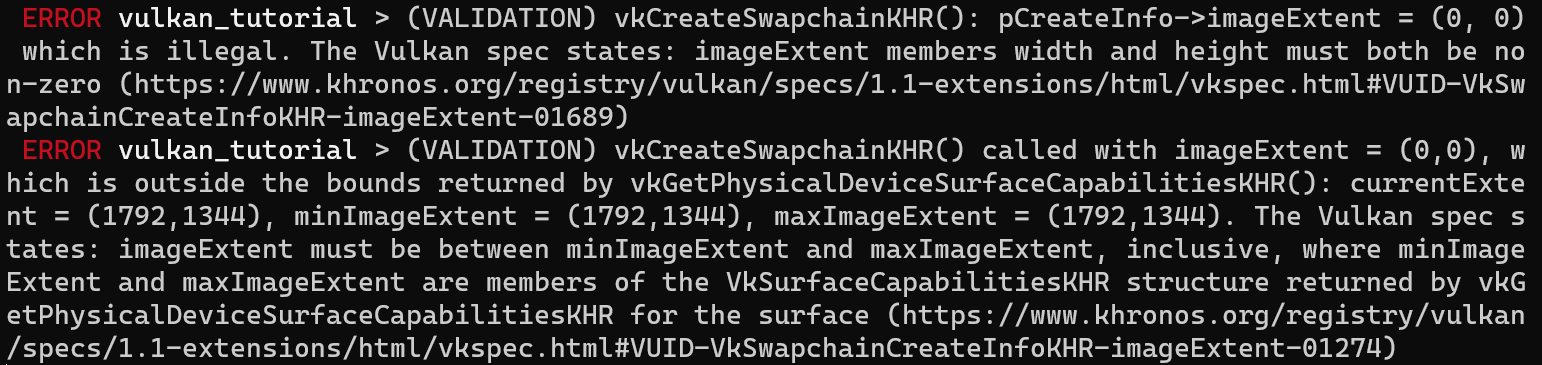

Try removing the .image_extent(extent) line from where you are building the vk::SwapchainCreateInfoKHR struct with validation layers enabled. You'll see that one of the validation layers immediately catches the mistake and some helpful messages are printed which call out the illegal value provided for image_extent:

Retrieving the swapchain images

The swapchain has been created now, so all that remains is retrieving the handles of the vk::Images in it. We'll reference these during rendering operations in later chapters. Add an AppData field to store the handles:

struct AppData {

// ...

swapchain_images: Vec<vk::Image>,

}

The images were created by the implementation for the swapchain and they will be automatically cleaned up once the swapchain has been destroyed, therefore we don't need to add any cleanup code.

I'm adding the code to retrieve the handles to the end of the create_swapchain function, right after the create_swapchain_khr call.

data.swapchain_images = device.get_swapchain_images_khr(data.swapchain)?;

One last thing, store the format and extent we've chosen for the swapchain images in AppData fields. We'll need them in future chapters.

struct AppData {

// ...

swapchain_format: vk::Format,

swapchain_extent: vk::Extent2D,

swapchain: vk::SwapchainKHR,

swapchain_images: Vec<vk::Image>,

}

And then in create_swapchain:

data.swapchain_format = surface_format.format;

data.swapchain_extent = extent;

We now have a set of images that can be drawn onto and can be presented to the window. The next chapter will begin to cover how we can set up the images as render targets and then we start looking into the actual graphics pipeline and drawing commands!