Fixed functions

Code: main.rs

The older graphics APIs provided default state for most of the stages of the graphics pipeline. In Vulkan you have to be explicit about everything, from viewport size to color blending function. In this chapter we'll fill in all of the structures to configure these fixed-function operations.

Vertex input

The vk::PipelineVertexInputStateCreateInfo structure describes the format of the vertex data that will be passed to the vertex shader. It describes this in roughly two ways:

- Bindings – spacing between data and whether the data is per-vertex or per-instance (see instancing)

- Attribute descriptions – type of the attributes passed to the vertex shader, which binding to load them from and at which offset

Because we're hard coding the vertex data directly in the vertex shader, we'll leave this structure with the defaults to specify that there is no vertex data to load for now. We'll get back to it in the vertex buffer chapter. Add this to the create_pipeline function right after the vk::PipelineShaderStageCreateInfo structs:

unsafe fn create_pipeline(device: &Device, data: &mut AppData) -> Result<()> {

// ...

let vertex_input_state = vk::PipelineVertexInputStateCreateInfo::builder();

The vertex_binding_descriptions and vertex_attribute_descriptions fields for this struct that could have been set here would be slices of structs that describe the aforementioned details for loading vertex data.

Input assembly

The vk::PipelineInputAssemblyStateCreateInfo struct describes two things: what kind of geometry will be drawn from the vertices and if primitive restart should be enabled. The former is specified in the topology member and can have values like:

vk::PrimitiveTopology::POINT_LIST– points from verticesvk::PrimitiveTopology::LINE_LIST– line from every 2 vertices without reusevk::PrimitiveTopology::LINE_STRIP– the end vertex of every line is used as start vertex for the next linevk::PrimitiveTopology::TRIANGLE_LIST– triangle from every 3 vertices without reusevk::PrimitiveTopology::TRIANGLE_STRIP– the second and third vertex of every triangle are used as first two vertices of the next triangle

Normally, the vertices are loaded from the vertex buffer by index in sequential order, but with an element buffer you can specify the indices to use yourself. This allows you to perform optimizations like reusing vertices. If you set the primitive_restart_enable member to true, then it's possible to break up lines and triangles in the _STRIP topology modes by using a special index of 0xFFFF or 0xFFFFFFFF.

We intend to draw triangles throughout this tutorial, so we'll stick to the following data for the structure:

let input_assembly_state = vk::PipelineInputAssemblyStateCreateInfo::builder()

.topology(vk::PrimitiveTopology::TRIANGLE_LIST)

.primitive_restart_enable(false);

Viewports and scissors

A viewport basically describes the region of the framebuffer that the output will be rendered to. This will almost always be (0, 0) to (width, height) and in this tutorial that will also be the case.

let viewport = vk::Viewport::builder()

.x(0.0)

.y(0.0)

.width(data.swapchain_extent.width as f32)

.height(data.swapchain_extent.height as f32)

.min_depth(0.0)

.max_depth(1.0);

Remember that the size of the swapchain and its images may differ from the WIDTH and HEIGHT of the window. The swapchain images will be used as framebuffers later on, so we should stick to their size.

The min_depth and max_depth values specify the range of depth values to use for the framebuffer. These values must be within the [0.0, 1.0] range, but min_depth may be higher than max_depth. If you aren't doing anything special, then you should stick to the standard values of 0.0 and 1.0.

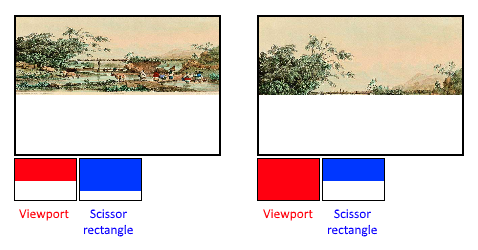

While viewports define the transformation from the image to the framebuffer, scissor rectangles define in which regions pixels will actually be stored. Any pixels outside the scissor rectangles will be discarded by the rasterizer. They function like a filter rather than a transformation. The difference is illustrated below. Note that the left scissor rectangle is just one of the many possibilities that would result in that image, as long as it's larger than the viewport.

In this tutorial we simply want to draw to the entire framebuffer, so we'll specify a scissor rectangle that covers it entirely:

let scissor = vk::Rect2D::builder()

.offset(vk::Offset2D { x: 0, y: 0 })

.extent(data.swapchain_extent);

Now this viewport and scissor rectangle need to be combined into a viewport state using the vk::PipelineViewportStateCreateInfo struct. It is possible to use multiple viewports and scissor rectangles on some graphics cards, so its members reference an array of them. Using multiple requires enabling a GPU feature (see logical device creation).

let viewports = &[viewport];

let scissors = &[scissor];

let viewport_state = vk::PipelineViewportStateCreateInfo::builder()

.viewports(viewports)

.scissors(scissors);

Rasterizer

The rasterizer takes the geometry that is shaped by the vertices from the vertex shader and turns it into fragments to be colored by the fragment shader. It also performs depth testing, face culling and the scissor test, and it can be configured to output fragments that fill entire polygons or just the edges (wireframe rendering). All this is configured using the vk::PipelineRasterizationStateCreateInfo structure.

let rasterization_state = vk::PipelineRasterizationStateCreateInfo::builder()

.depth_clamp_enable(false)

// continued...

If depth_clamp_enable is set to true, then fragments that are beyond the near and far planes are clamped to them as opposed to discarding them. This is useful in some special cases like shadow maps. Using this requires enabling a GPU feature.

.rasterizer_discard_enable(false)

If rasterizer_discard_enable is set to true, then geometry never passes through the rasterizer stage. This basically disables any output to the framebuffer.

.polygon_mode(vk::PolygonMode::FILL)

The polygon_mode determines how fragments are generated for geometry. The following modes are available:

vk::PolygonMode::FILL– fill the area of the polygon with fragmentsvk::PolygonMode::LINE– polygon edges are drawn as linesvk::PolygonMode::POINT– polygon vertices are drawn as points

Using any mode other than fill requires enabling a GPU feature.

.line_width(1.0)

The line_width member is straightforward, it describes the thickness of lines in terms of number of fragments. The maximum line width that is supported depends on the hardware and any line thicker than 1.0 requires you to enable the wide_lines GPU feature.

.cull_mode(vk::CullModeFlags::BACK)

.front_face(vk::FrontFace::CLOCKWISE)

The cull_mode variable determines the type of face culling to use. You can disable culling, cull the front faces, cull the back faces or both. The front_face variable specifies the vertex order for faces to be considered front-facing and can be clockwise or counterclockwise.

.depth_bias_enable(false);

The rasterizer can alter the depth values by adding a constant value or biasing them based on a fragment's slope. This is sometimes used for shadow mapping, but we won't be using it. Just set depth_bias_enable to false.

Multisampling

The vk::PipelineMultisampleStateCreateInfo struct configures multisampling, which is one of the ways to perform anti-aliasing. It works by combining the fragment shader results of multiple polygons that rasterize to the same pixel. This mainly occurs along edges, which is also where the most noticeable aliasing artifacts occur. Because it doesn't need to run the fragment shader multiple times if only one polygon maps to a pixel, it is significantly less expensive than simply rendering to a higher resolution and then downscaling. Enabling it requires enabling a GPU feature.

let multisample_state = vk::PipelineMultisampleStateCreateInfo::builder()

.sample_shading_enable(false)

.rasterization_samples(vk::SampleCountFlags::_1);

We'll revisit multisampling in a later chapter, for now let's keep it disabled.

Depth and stencil testing

If you are using a depth and/or stencil buffer, then you also need to configure the depth and stencil tests using vk::PipelineDepthStencilStateCreateInfo. We don't have one right now, so we can simply ignore it for now. We'll get back to it in the depth buffering chapter.

Color blending

After a fragment shader has returned a color, it needs to be combined with the color that is already in the framebuffer. This transformation is known as color blending and there are two ways to do it:

- Mix the old and new value to produce a final color

- Combine the old and new value using a bitwise operation

There are two types of structs to configure color blending. The first struct, vk::PipelineColorBlendAttachmentState contains the configuration per attached framebuffer and the second struct, vk::PipelineColorBlendStateCreateInfo contains the global color blending settings. In our case we only have one framebuffer:

let attachment = vk::PipelineColorBlendAttachmentState::builder()

.color_write_mask(vk::ColorComponentFlags::all())

.blend_enable(false)

.src_color_blend_factor(vk::BlendFactor::ONE) // Optional

.dst_color_blend_factor(vk::BlendFactor::ZERO) // Optional

.color_blend_op(vk::BlendOp::ADD) // Optional

.src_alpha_blend_factor(vk::BlendFactor::ONE) // Optional

.dst_alpha_blend_factor(vk::BlendFactor::ZERO) // Optional

.alpha_blend_op(vk::BlendOp::ADD); // Optional

This per-framebuffer struct allows you to configure the first way of color blending. The operations that will be performed are best demonstrated using the following pseudocode:

if blend_enable {

final_color.rgb = (src_color_blend_factor * new_color.rgb)

<color_blend_op> (dst_color_blend_factor * old_color.rgb);

final_color.a = (src_alpha_blend_factor * new_color.a)

<alpha_blend_op> (dst_alpha_blend_factor * old_color.a);

} else {

final_color = new_color;

}

final_color = final_color & color_write_mask;

If blend_enable is set to false, then the new color from the fragment shader is passed through unmodified. Otherwise, the two mixing operations are performed to compute a new color. The resulting color is AND'd with the color_write_mask to determine which channels are actually passed through.

The most common way to use color blending is to implement alpha blending, where we want the new color to be blended with the old color based on its opacity. The final_color should then be computed as follows:

final_color.rgb = new_alpha * new_color + (1 - new_alpha) * old_color;

final_color.a = new_alpha.a;

This can be accomplished with the following parameters:

let attachment = vk::PipelineColorBlendAttachmentState::builder()

.color_write_mask(vk::ColorComponentFlags::all())

.blend_enable(true)

.src_color_blend_factor(vk::BlendFactor::SRC_ALPHA)

.dst_color_blend_factor(vk::BlendFactor::ONE_MINUS_SRC_ALPHA)

.color_blend_op(vk::BlendOp::ADD)

.src_alpha_blend_factor(vk::BlendFactor::ONE)

.dst_alpha_blend_factor(vk::BlendFactor::ZERO)

.alpha_blend_op(vk::BlendOp::ADD);

You can find all of the possible operations in the vk::BlendFactor and vk::BlendOp enumerations in the specification (or vulkanalia's documentation).

The second structure references the array of structures for all of the framebuffers and allows you to set blend constants that you can use as blend factors in the aforementioned calculations.

let attachments = &[attachment];

let color_blend_state = vk::PipelineColorBlendStateCreateInfo::builder()

.logic_op_enable(false)

.logic_op(vk::LogicOp::COPY)

.attachments(attachments)

.blend_constants([0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0]);

If you want to use the second method of blending (bitwise combination), then you should set logic_op_enable to true. The bitwise operation can then be specified in the logic_op field. Note that this will automatically disable the first method, as if you had set blend_enable to false for every attached framebuffer! The color_write_mask will also be used in this mode to determine which channels in the framebuffer will actually be affected. It is also possible to disable both modes, as we've done here, in which case the fragment colors will be written to the framebuffer unmodified.

Dynamic state (example, don't add)

A limited amount of the state that we've specified in the previous structs can actually be changed without recreating the pipeline. Examples are the size of the viewport, line width and blend constants. If you want to do that, then you'll have to fill in a vk::PipelineDynamicStateCreateInfo structure like this:

let dynamic_states = &[

vk::DynamicState::VIEWPORT,

vk::DynamicState::LINE_WIDTH,

];

let dynamic_state = vk::PipelineDynamicStateCreateInfo::builder()

.dynamic_states(dynamic_states);

This will cause the configuration of these values to be ignored and you will be required to specify the data at drawing time. We'll get back to this in a future chapter. This struct can be omitted if you don't have any dynamic state.

Pipeline layout

You can use uniform values in shaders, which are globals similar to dynamic state variables that can be changed at drawing time to alter the behavior of your shaders without having to recreate them. They are commonly used to pass the transformation matrix to the vertex shader, or to create texture samplers in the fragment shader.

These uniform values need to be specified during pipeline creation by creating a vk::PipelineLayout object. Even though we won't be using them until a future chapter, we are still required to create an empty pipeline layout.

Create an AppData field to hold this object, because we'll refer to it from other functions at a later point in time:

struct AppData {

// ...

pipeline_layout: vk::PipelineLayout,

}

And then create the object in the create_pipeline function just above the calls to destroy_shader_module:

unsafe fn create_pipeline(device: &Device, data: &mut AppData) -> Result<()> {

// ...

let layout_info = vk::PipelineLayoutCreateInfo::builder();

data.pipeline_layout = device.create_pipeline_layout(&layout_info, None)?;

device.destroy_shader_module(vert_shader_module, None);

device.destroy_shader_module(frag_shader_module, None);

Ok(())

}

The structure also specifies push constants, which are another way of passing dynamic values to shaders that we may get into in a future chapter. The pipeline layout will be referenced throughout the program's lifetime, so it should be destroyed in App::destroy:

unsafe fn destroy(&mut self) {

self.device.destroy_pipeline_layout(self.data.pipeline_layout, None);

// ...

}

Conclusion

That's it for all of the fixed-function state! It's a lot of work to set all of this up from scratch, but the advantage is that we're now nearly fully aware of everything that is going on in the graphics pipeline! This reduces the chance of running into unexpected behavior because the default state of certain components is not what you expect.

There is however one more object to create before we can finally create the graphics pipeline and that is a render pass.