Push constants

The previous chapters of this tutorial that are not marked by this disclaimer were directly adapted from https://github.com/Overv/VulkanTutorial.

This chapter and the following chapters are instead original creations from someone who is most decidedly not an expert in Vulkan. An authoritative tone has been maintained, but these chapters should be considered a "best effort" by someone still learning Vulkan.

If you have questions, suggestions, or corrections, please open an issue!

Code: main.rs | shader.vert | shader.frag

The scene that we've created in the tutorial thus far is static. While we can rotate and otherwise move the model around on the screen by manipulating the uniform buffers that provide the model, view, and projection (MVP) matrices, we can't alter what is being rendered. This is because the decision of what to render is made during program initialization when our command buffers are allocated and recorded.

In the next few chapters we are going to explore various techniques we can use to accomplish the rendering of dynamic scenes. First, however, we are going to look at push constants, a Vulkan feature that allows us to easily and efficiently "push" dynamic data to shaders. Push constants alone will not accomplish our goal of a dynamic scene, but their usefulness should become clear over the next few chapters.

Push constants vs uniform buffers

We are already using another Vulkan feature to provide dynamic data to our vertex shader: uniform buffers. Every frame, the App::update_uniform_buffer method calculates the updated MVP matrices for the model's current rotation and copies those matrices to a uniform buffer. The vertex shader then reads those matrices from the uniform buffer to figure out where the vertices of the model belong on the screen.

This approach works well enough, when would we want to use push constants instead? One advantage of push constants over uniform buffers is speed, updating a push constant will usually be significantly faster than copying new data to a uniform buffer. For a large number of values that need to be updated frequently, this difference can add up quickly.

Of course there is a catch: the amount of data that can be provided to a shader using push constants has a very limited maximum size. This maximum size varies from device to device and is specified in bytes by the max_push_constants_size field of vk::PhysicalDeviceLimits. Vulkan requires that this limit be at least 128 bytes (see table 32), but you won't find values much larger than that in the wild. Even high-end hardware like the RTX 3080 only has a limit of 256 bytes.

If we wanted to, say, use push constants to provide our MVP matrices to our shaders we would immediately run into this limitation. The MVP matrices are too large to reliably fit in push constants, each matrix is 64 bytes (16 × 4 byte floats) leading to a total of 192 bytes. Of course we could maintain two code paths, one for devices that can handle push constants >= 192 bytes and another for devices that can't, but there are simpler approaches we could take.

One would be to premultiply our MVP matrices into a single matrix. Another would be to provide only the model matrix as a push constant and leave the view and projection matrices in the uniform buffer. Both would give us at least 64 bytes of headroom for other push constants even on devices providing only the minimum 128 bytes for push constants. In this chapter we will take the second approach to start exploring push constants.

Why only the model matrix for the second approach? In the App::update_uniform_buffer method, you'll notice that the model matrix changes every frame as time increases, the view matrix is static, and the proj matrix only changes when the window is resized. This would allow us to only update the uniform buffer containing the view and projection matrices when the window is resized and use push constants to provide the constantly changing model matrix.

Of course, in a more realistic application the view matrix would most likely not be static. For example, if you were building a first-person game, the view matrix would change very frequently as the player moves through the game world. However, the view and projection matrices, even if they change every frame, would be shared between all or at least most of the models you are rendering. This means you could continue updating the uniform buffer once per frame to provide the shared view and projection matrices and use push constants to provide the model matrices for each model in your scene.

Pushing the model matrix

With that wall of text out of the way, let's get started by moving the model matrix in the vertex shader from the uniform buffer object to a push constant. Don't forget to recompile the vertex shader afterwards!

#version 450

layout(binding = 0) uniform UniformBufferObject {

mat4 view;

mat4 proj;

} ubo;

layout(push_constant) uniform PushConstants {

mat4 model;

} pcs;

// ...

void main() {

gl_Position = ubo.proj * ubo.view * pcs.model * vec4(inPosition, 1.0);

// ...

}

Note that the layout is push_constant and not something like push_constant = 0 like how the uniform buffer object is defined. This is because we can only provide one collection of push constants for an invocation of a graphics pipeline and this collection is very limited in size as described previously.

Remove model from the UniformBufferObject struct since we will be specifying it as a push constant from here on out.

#[repr(C)]

#[derive(Copy, Clone, Debug)]

struct UniformBufferObject {

view: Mat4,

proj: Mat4,

}

Also remove model from the App::update_uniform_buffer method.

let view = Mat4::look_at_rh(

point3(2.0, 2.0, 2.0),

point3(0.0, 0.0, 0.0),

vec3(0.0, 0.0, 1.0),

);

let correction = Mat4::new(

1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0,

0.0, -1.0, 0.0, 0.0,

0.0, 0.0, 1.0 / 2.0, 0.0,

0.0, 0.0, 1.0 / 2.0, 1.0,

);

let proj = correction * cgmath::perspective(

Deg(45.0),

self.data.swapchain_extent.width as f32 / self.data.swapchain_extent.height as f32,

0.1,

10.0,

);

let ubo = UniformBufferObject { view, proj };

// ...

We need to tell Vulkan about our new push constant by describing it in the layout of our graphics pipeline. In the create_pipeline function you'll see that we are already providing our descriptor set layout to create_pipeline_layout. This descriptor set layout describes the uniform buffer object and texture sampler used in our shaders and we need to similarly describe any push constants accessed by the shaders in our graphics pipeline using vk::PushConstantRange.

let vert_push_constant_range = vk::PushConstantRange::builder()

.stage_flags(vk::ShaderStageFlags::VERTEX)

.offset(0)

.size(64 /* 16 × 4 byte floats */);

let set_layouts = &[data.descriptor_set_layout];

let push_constant_ranges = &[vert_push_constant_range];

let layout_info = vk::PipelineLayoutCreateInfo::builder()

.set_layouts(set_layouts)

.push_constant_ranges(push_constant_ranges);

data.pipeline_layout = device.create_pipeline_layout(&layout_info, None)?;

The push constant range here specifies that the push constants accessed by the vertex shader can be found at the beginning of the push constants provided to the graphics pipeline and are the size of a mat4.

With all that in place, we can actually start pushing the model matrix to the vertex shader. Push constants are recorded directly into the command buffers submitted to the GPU which is both why they are so fast and why their size is so limited.

In the create_command_buffers function, define a model matrix and use cmd_push_constants to add it to the command buffers as a push constant right before we record the draw command.

let model = Mat4::from_axis_angle(

vec3(0.0, 0.0, 1.0),

Deg(0.0)

);

let model_bytes = std::slice::from_raw_parts(

&model as *const Mat4 as *const u8,

size_of::<Mat4>()

);

for (i, command_buffer) in data.command_buffers.iter().enumerate() {

// ...

device.cmd_push_constants(

*command_buffer,

data.pipeline_layout,

vk::ShaderStageFlags::VERTEX,

0,

model_bytes,

);

device.cmd_draw_indexed(*command_buffer, data.indices.len() as u32, 1, 0, 0, 0);

// ...

}

If you run the program now you will see the familiar model, but it is no longer rotating! Instead of updating the model matrix in the uniform buffer object every frame we are now encoding it into the command buffers which, as previously discussed, are never updated. This further highlights the need to somehow update our command buffers, a topic that will be covered in the next chapter. For now, let's round out this chapter by adding a push constant to the fragment shader.

Pushing the opacity

Next we'll add a push constant to the fragment shader which we can use to control the opacity of the model. Start by modifying the fragment shader to include the push constant and to use it as the alpha channel of the fragment color. Again, be sure to recompile the shader!

#version 450

layout(binding = 1) uniform sampler2D texSampler;

layout(push_constant) uniform PushConstants {

layout(offset = 64) float opacity;

} pcs;

// ...

void main() {

outColor = vec4(texture(texSampler, fragTexCoord).rgb, pcs.opacity);

}

This time we specify an offset for the push constant value. Remember that push constants are shared between all of the shaders in a graphics pipeline so we need to account for the fact that the first 64 bytes of the push constants are occupied by the model matrix used in the vertex shader.

Add a push constant range for the new opacity push constant to the pipeline layout.

let vert_push_constant_range = vk::PushConstantRange::builder()

.stage_flags(vk::ShaderStageFlags::VERTEX)

.offset(0)

.size(64 /* 16 × 4 byte floats */);

let frag_push_constant_range = vk::PushConstantRange::builder()

.stage_flags(vk::ShaderStageFlags::FRAGMENT)

.offset(64)

.size(4);

let set_layouts = &[data.descriptor_set_layout];

let push_constant_ranges = &[vert_push_constant_range, frag_push_constant_range];

let layout_info = vk::PipelineLayoutCreateInfo::builder()

.set_layouts(set_layouts)

.push_constant_ranges(push_constant_ranges);

data.pipeline_layout = device.create_pipeline_layout(&layout_info, None)?;

Lastly, add another call to cmd_push_constants in the create_command_buffers after the call for the model matrix.

device.cmd_push_constants(

*command_buffer,

data.pipeline_layout,

vk::ShaderStageFlags::VERTEX,

0,

model_bytes,

);

device.cmd_push_constants(

*command_buffer,

data.pipeline_layout,

vk::ShaderStageFlags::FRAGMENT,

64,

&0.25f32.to_ne_bytes()[..],

);

device.cmd_draw_indexed(*command_buffer, data.indices.len() as u32, 1, 0, 0, 0);

Here we provide an opacity of 0.25 to the fragment shader by recording it into the command buffer after the 64 bytes of the model matrix. However, if you were to run the program now, you'd find that the model is still entirely opaque!

Back in the chapter on fixed function operations, we discussed what was necessary to set up alpha blending so that we could render transparent geometries to the framebuffers. However, back then we left alpha blending disabled. Update the vk::PipelineColorBlendAttachmentState in the create_pipeline function to enable alpha blending as described in that chapter.

let attachment = vk::PipelineColorBlendAttachmentState::builder()

.color_write_mask(vk::ColorComponentFlags::all())

.blend_enable(true)

.src_color_blend_factor(vk::BlendFactor::SRC_ALPHA)

.dst_color_blend_factor(vk::BlendFactor::ONE_MINUS_SRC_ALPHA)

.color_blend_op(vk::BlendOp::ADD)

.src_alpha_blend_factor(vk::BlendFactor::ONE)

.dst_alpha_blend_factor(vk::BlendFactor::ZERO)

.alpha_blend_op(vk::BlendOp::ADD);

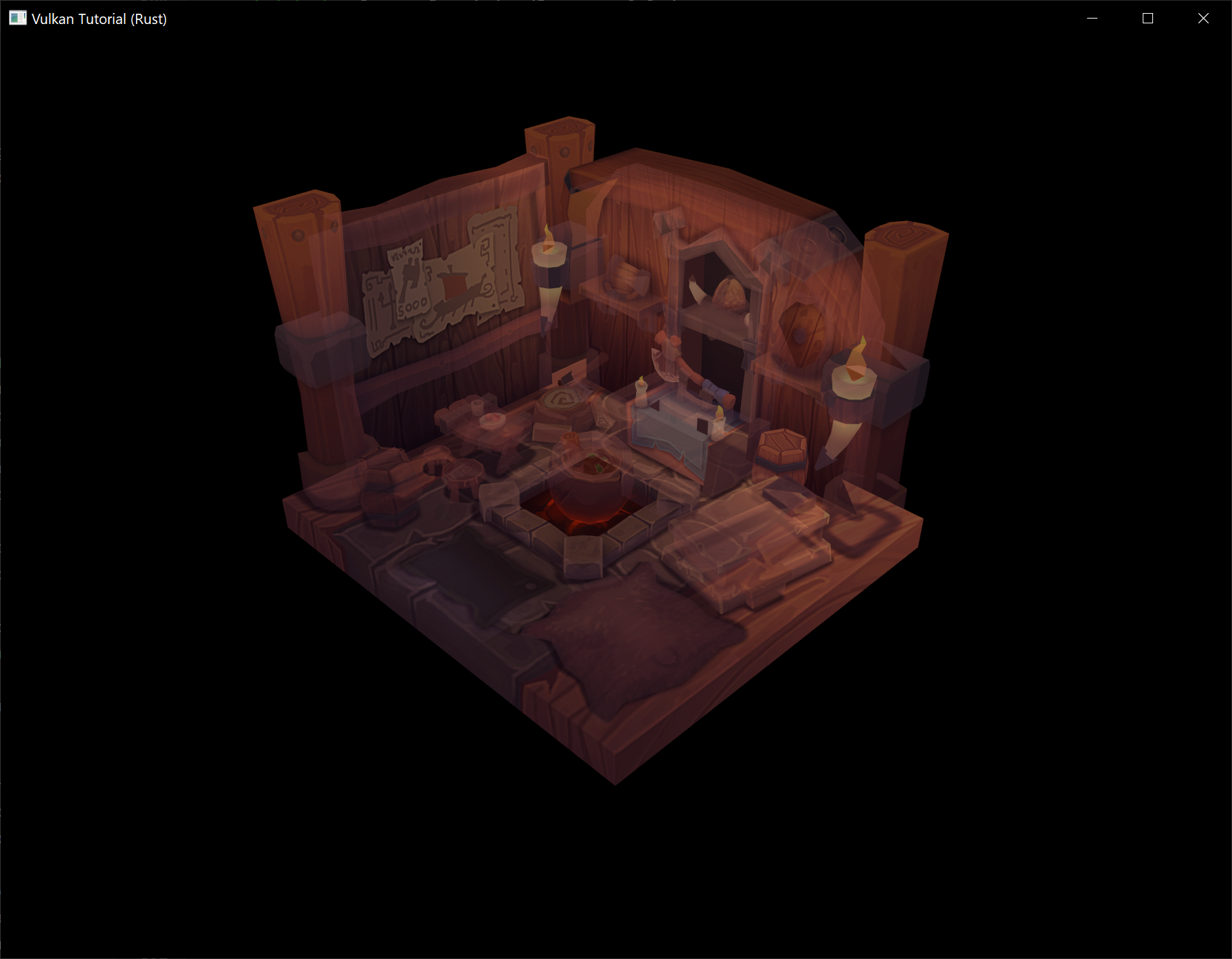

Run the program to see our now ghostly model.

Success!