Shader modules

Code: main.rs | shader.vert | shader.frag

Unlike earlier APIs, shader code in Vulkan has to be specified in a bytecode format as opposed to human-readable syntax like GLSL and HLSL. This bytecode format is called SPIR-V and is designed to be used with both Vulkan and OpenCL (both Khronos APIs). It is a format that can be used to write graphics and compute shaders, but we will focus on shaders used in Vulkan's graphics pipelines in this tutorial.

The advantage of using a bytecode format is that the compilers written by GPU vendors to turn shader code into native code are significantly less complex. The past has shown that with human-readable syntax like GLSL, some GPU vendors were rather flexible with their interpretation of the standard. If you happen to write non-trivial shaders with a GPU from one of these vendors, then you'd risk other vendor's drivers rejecting your code due to syntax errors, or worse, your shader running differently because of compiler bugs. With a straightforward bytecode format like SPIR-V that will hopefully be avoided.

However, that does not mean that we need to write this bytecode by hand. Khronos has released their own vendor-independent compiler that compiles GLSL to SPIR-V. This compiler is designed to verify that your shader code is fully standards compliant and produces one SPIR-V binary that you can ship with your program. You can also include this compiler as a library to produce SPIR-V at runtime, but we won't be doing that in this tutorial. Although we can use this compiler directly via glslangValidator.exe, we will be using glslc.exe by Google instead. The advantage of glslc is that it uses the same parameter format as well-known compilers like GCC and Clang and includes some extra functionality like includes. Both of them are already included in the Vulkan SDK, so you don't need to download anything extra.

GLSL is a shading language with a C-style syntax. Programs written in it have a main function that is invoked for every object. Instead of using parameters for input and a return value as output, GLSL uses global variables to handle input and output. The language includes many features to aid in graphics programming, like built-in vector and matrix primitives. Functions for operations like cross products, matrix-vector products and reflections around a vector are included. The vector type is called vec with a number indicating the amount of elements. For example, a 3D position would be stored in a vec3. It is possible to access single components through fields like .x, but it's also possible to create a new vector from multiple components at the same time. For example, the expression vec3(1.0, 2.0, 3.0).xy would result in vec2. The constructors of vectors can also take combinations of vector objects and scalar values. For example, a vec3 can be constructed with vec3(vec2(1.0, 2.0), 3.0).

As the previous chapter mentioned, we need to write a vertex shader and a fragment shader to get a triangle on the screen. The next two sections will cover the GLSL code of each of those and after that I'll show you how to produce two SPIR-V binaries and load them into the program.

Vertex shader

The vertex shader processes each incoming vertex. It takes its attributes, like world position, color, normal and texture coordinates as input. The output is the final position in clip coordinates and the attributes that need to be passed on to the fragment shader, like color and texture coordinates. These values will then be interpolated over the fragments by the rasterizer to produce a smooth gradient.

A clip coordinate is a four dimensional vector from the vertex shader that is subsequently turned into a normalized device coordinate by dividing the whole vector by its last component. These normalized device coordinates are homogeneous coordinates that map the framebuffer to a [-1, 1] by [-1, 1] coordinate system that looks like the following:

You should already be familiar with these if you have dabbled in computer graphics before. If you have used OpenGL before, then you'll notice that the sign of the Y coordinates is now flipped. The Z coordinate now uses the same range as it does in Direct3D, from 0 to 1.

For our first triangle we won't be applying any transformations, we'll just specify the positions of the three vertices directly as normalized device coordinates to create the following shape:

We can directly output normalized device coordinates by outputting them as clip coordinates from the vertex shader with the last component set to 1. That way the division to transform clip coordinates to normalized device coordinates will not change anything.

Normally these coordinates would be stored in a vertex buffer, but creating a vertex buffer in Vulkan and filling it with data is not trivial. Therefore I've decided to postpone that until after we've had the satisfaction of seeing a triangle pop up on the screen. We're going to do something a little unorthodox in the meanwhile: include the coordinates directly inside the vertex shader. The code looks like this:

#version 450

vec2 positions[3] = vec2[](

vec2(0.0, -0.5),

vec2(0.5, 0.5),

vec2(-0.5, 0.5)

);

void main() {

gl_Position = vec4(positions[gl_VertexIndex], 0.0, 1.0);

}

The main function is invoked for every vertex. The built-in gl_VertexIndex variable contains the index of the current vertex. This is usually an index into the vertex buffer, but in our case it will be an index into a hardcoded array of vertex data. The position of each vertex is accessed from the constant array in the shader and combined with dummy z and w components to produce a position in clip coordinates. The built-in variable gl_Position functions as the output.

Fragment shader

The triangle that is formed by the positions from the vertex shader fills an area on the screen with fragments. The fragment shader is invoked on these fragments to produce a color and depth for the framebuffer (or framebuffers). A simple fragment shader that outputs the color red for the entire triangle looks like this:

#version 450

layout(location = 0) out vec4 outColor;

void main() {

outColor = vec4(1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0);

}

The main function is called for every fragment just like the vertex shader main function is called for every vertex. Colors in GLSL are 4-component vectors with the R, G, B and alpha channels within the [0, 1] range. Unlike gl_Position in the vertex shader, there is no built-in variable to output a color for the current fragment. You have to specify your own output variable for each framebuffer where the layout(location = 0) modifier specifies the index of the framebuffer. The color red is written to this outColor variable that is linked to the first (and only) framebuffer at index 0.

Per-vertex colors

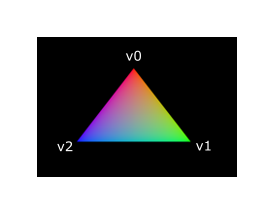

Making the entire triangle red is not very interesting, wouldn't something like the following look a lot nicer?

We have to make a couple of changes to both shaders to accomplish this. First off, we need to specify a distinct color for each of the three vertices. The vertex shader should now include an array with colors just like it does for positions:

vec3 colors[3] = vec3[](

vec3(1.0, 0.0, 0.0),

vec3(0.0, 1.0, 0.0),

vec3(0.0, 0.0, 1.0)

);

Now we just need to pass these per-vertex colors to the fragment shader so it can output their interpolated values to the framebuffer. Add an output for color to the vertex shader and write to it in the main function:

layout(location = 0) out vec3 fragColor;

void main() {

gl_Position = vec4(positions[gl_VertexIndex], 0.0, 1.0);

fragColor = colors[gl_VertexIndex];

}

Next, we need to add a matching input in the fragment shader:

layout(location = 0) in vec3 fragColor;

void main() {

outColor = vec4(fragColor, 1.0);

}

The input variable does not necessarily have to use the same name, they will be linked together using the indexes specified by the location directives. The main function has been modified to output the color along with an alpha value. As shown in the image above, the values for fragColor will be automatically interpolated for the fragments between the three vertices, resulting in a smooth gradient.

Compiling the shaders

Create a directory called shaders in the root directory of your project (adjacent to the src directory) and store the vertex shader in a file called shader.vert and the fragment shader in a file called shader.frag in that directory. GLSL shaders don't have an official extension, but these two are commonly used to distinguish them.

The contents of shader.vert should be:

#version 450

layout(location = 0) out vec3 fragColor;

vec2 positions[3] = vec2[](

vec2(0.0, -0.5),

vec2(0.5, 0.5),

vec2(-0.5, 0.5)

);

vec3 colors[3] = vec3[](

vec3(1.0, 0.0, 0.0),

vec3(0.0, 1.0, 0.0),

vec3(0.0, 0.0, 1.0)

);

void main() {

gl_Position = vec4(positions[gl_VertexIndex], 0.0, 1.0);

fragColor = colors[gl_VertexIndex];

}

And the contents of shader.frag should be:

#version 450

layout(location = 0) in vec3 fragColor;

layout(location = 0) out vec4 outColor;

void main() {

outColor = vec4(fragColor, 1.0);

}

We're now going to compile these into SPIR-V bytecode using the glslc program.

Windows

Create a compile.bat file with the following contents:

C:/VulkanSDK/x.x.x.x/Bin32/glslc.exe shader.vert -o vert.spv

C:/VulkanSDK/x.x.x.x/Bin32/glslc.exe shader.frag -o frag.spv

pause

Replace the path to glslc.exe with the path to where you installed the Vulkan SDK. Double click the file to run it.

Linux

Create a compile.sh file with the following contents:

/home/user/VulkanSDK/x.x.x.x/x86_64/bin/glslc shader.vert -o vert.spv

/home/user/VulkanSDK/x.x.x.x/x86_64/bin/glslc shader.frag -o frag.spv

Replace the path to glslc with the path to where you installed the Vulkan SDK. Make the script executable with chmod +x compile.sh and run it.

macOS

Create a compile.sh file with the following contents:

/Users/user/VulkanSDK/x.x.x.x/macOS/bin/glslc shaders/shader.vert -o vert.spv

/Users/user/VulkanSDK/x.x.x.x/macOS/bin/glslc shaders/shader.frag -o frag.spv

End of platform-specific instructions

These two commands tell the compiler to read the GLSL source file and output a SPIR-V bytecode file using the -o (output) flag.

If your shader contains a syntax error then the compiler will tell you the line number and problem, as you would expect. Try leaving out a semicolon for example and run the compile script again. Also try running the compiler without any arguments to see what kinds of flags it supports. It can, for example, also output the bytecode into a human-readable format so you can see exactly what your shader is doing and any optimizations that have been applied at this stage.

Compiling shaders on the commandline is one of the most straightforward options and it's the one that we'll use in this tutorial, but it's also possible to compile shaders directly from your own code. The Vulkan SDK includes libshaderc, which is a library to compile GLSL code to SPIR-V from within your program.

Loading a shader

Now that we have a way of producing SPIR-V shaders, it's time to bring them into our program to plug them into the graphics pipeline at some point. We'll start by using include_bytes! from the Rust standard library to include the compiled SPIR-V bytecode for the shaders in our executable.

unsafe fn create_pipeline(device: &Device, data: &mut AppData) -> Result<()> {

let vert = include_bytes!("../shaders/vert.spv");

let frag = include_bytes!("../shaders/frag.spv");

Ok(())

}

Creating shader modules

Before we can pass the code to the pipeline, we have to wrap it in a vk::ShaderModule object. Let's create a helper function create_shader_module to do that.

unsafe fn create_shader_module(

device: &Device,

bytecode: &[u8],

) -> Result<vk::ShaderModule> {

}

The function will take a slice containing the bytecode as parameter and create a vk::ShaderModule from it using our logical device.

Creating a shader module is simple, we only need to specify the length of our bytecode slice and the bytecode slice itself. This information is specified in a vk::ShaderModuleCreateInfo structure. The one catch is that the size of the bytecode is specified in bytes, but the bytecode slice expected by this struct is a &[u32] instead of a &[u8]. Therefore we will first need to convert our &[u8] into an &[u32].

vulkanalia has a helper struct called Bytecode that we will use to copy the shader bytecode into a new buffer that is guaranteed to have the correct alignment for an array of u32s. Add an import for this helper struct:

use vulkanalia::bytecode::Bytecode;

Getting back to our create_shader_module function, Bytecode::new will return an error if the supplied byte slice has a length that is not a multiple of 4 or if the allocation of the aligned buffer fails. As long as you are providing valid shader bytecode this should never be a problem, so we'll just unwrap the result.

let bytecode = Bytecode::new(bytecode).unwrap();

We can then construct a vk::ShaderModuleCreateInfo and use it to call create_shader_module to create the shader module:

let info = vk::ShaderModuleCreateInfo::builder()

.code(bytecode.code())

.code_size(bytecode.code_size());

Ok(device.create_shader_module(&info, None)?)

The parameters are the same as those in previous object creation functions: the create info structure and the optional custom allocators.

Shader modules are just a thin wrapper around the shader bytecode that we've previously loaded from a file and the functions defined in it. The compilation and linking of the SPIR-V bytecode to machine code for execution by the GPU doesn't happen until the graphics pipeline is created. That means that we're allowed to destroy the shader modules again as soon as pipeline creation is finished, which is why we'll make them local variables in the create_pipeline function instead of fields in AppData:

unsafe fn create_pipeline(device: &Device, data: &mut AppData) -> Result<()> {

let vert = include_bytes!("../shaders/vert.spv");

let frag = include_bytes!("../shaders/frag.spv");

let vert_shader_module = create_shader_module(device, &vert[..])?;

let frag_shader_module = create_shader_module(device, &frag[..])?;

// ...

The cleanup should then happen at the end of the function by adding two calls to destroy_shader_module. All of the remaining code in this chapter will be inserted before these lines.

// ...

device.destroy_shader_module(vert_shader_module, None);

device.destroy_shader_module(frag_shader_module, None);

Ok(())

}

Shader stage creation

To actually use the shaders we'll need to assign them to a specific pipeline stage through vk::PipelineShaderStageCreateInfo structures as part of the actual pipeline creation process.

We'll start by filling in the structure for the vertex shader, again in the create_pipeline function.

let vert_stage = vk::PipelineShaderStageCreateInfo::builder()

.stage(vk::ShaderStageFlags::VERTEX)

.module(vert_shader_module)

.name(b"main\0");

The first step is telling Vulkan in which pipeline stage the shader is going to be used. There is a variant for each of the programmable stages described in the previous chapter.

The next two fields specify the shader module containing the code, and the function to invoke, known as the entrypoint. That means that it's possible to combine multiple fragment shaders into a single shader module and use different entry points to differentiate between their behaviors. In this case we'll stick to the standard main, however.

There is one more (optional) member, specialization_info, which we won't be using here, but is worth discussing. It allows you to specify values for shader constants. You can use a single shader module where its behavior can be configured at pipeline creation by specifying different values for the constants used in it. This is more efficient than configuring the shader using variables at render time, because the compiler can do optimizations like eliminating if statements that depend on these values. If you don't have any constants like that, then you can just skip setting it as we are doing here.

Modifying the structure to suit the fragment shader is easy:

let frag_stage = vk::PipelineShaderStageCreateInfo::builder()

.stage(vk::ShaderStageFlags::FRAGMENT)

.module(frag_shader_module)

.name(b"main\0");

That's all there is to describing the programmable stages of the pipeline. In the next chapter we'll look at the fixed-function stages.